Department of the Treasury:

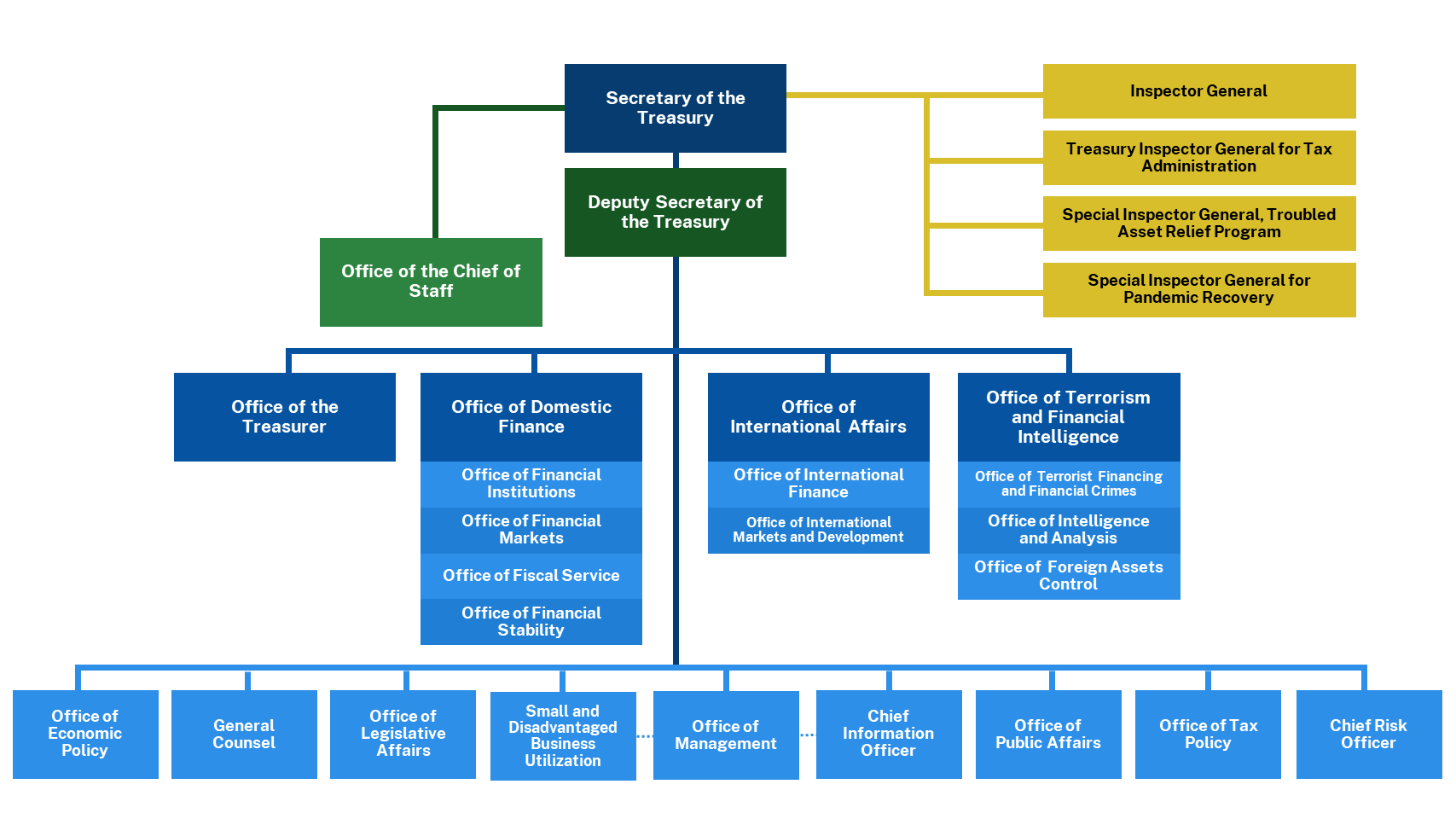

It Enforces finance and tax laws and manages Federal finances by collecting taxes and paying bills and by managing currency, government accounts and public debt.The Department of the Treasury is organized into two major components:

- Departmental offices

- Operating bureaus

The Departmental Offices are primarily responsible for the formulation of policy and management of the Department as a whole, while the operating bureaus carry out the specific operations assigned to the Department. The bureaus make up 98% of the Treasury work force. The basic functions of the Department of the Treasury include:

- Managing Federal finances

- Collecting taxes, duties and monies paid to and due to the U.S. and paying all bills of the U.S.

- Currency and coinage

- Managing Government accounts and the public debt

- Supervising national banks and thrift institutions

- Advising on domestic and international financial, monetary, economic, trade and tax policy

- Enforcing Federal finance and tax laws

- Investigating and prosecuting tax evaders, counterfeiters, and forgers

https://home.treasury.gov/about/general-information/role-of-the-treasury

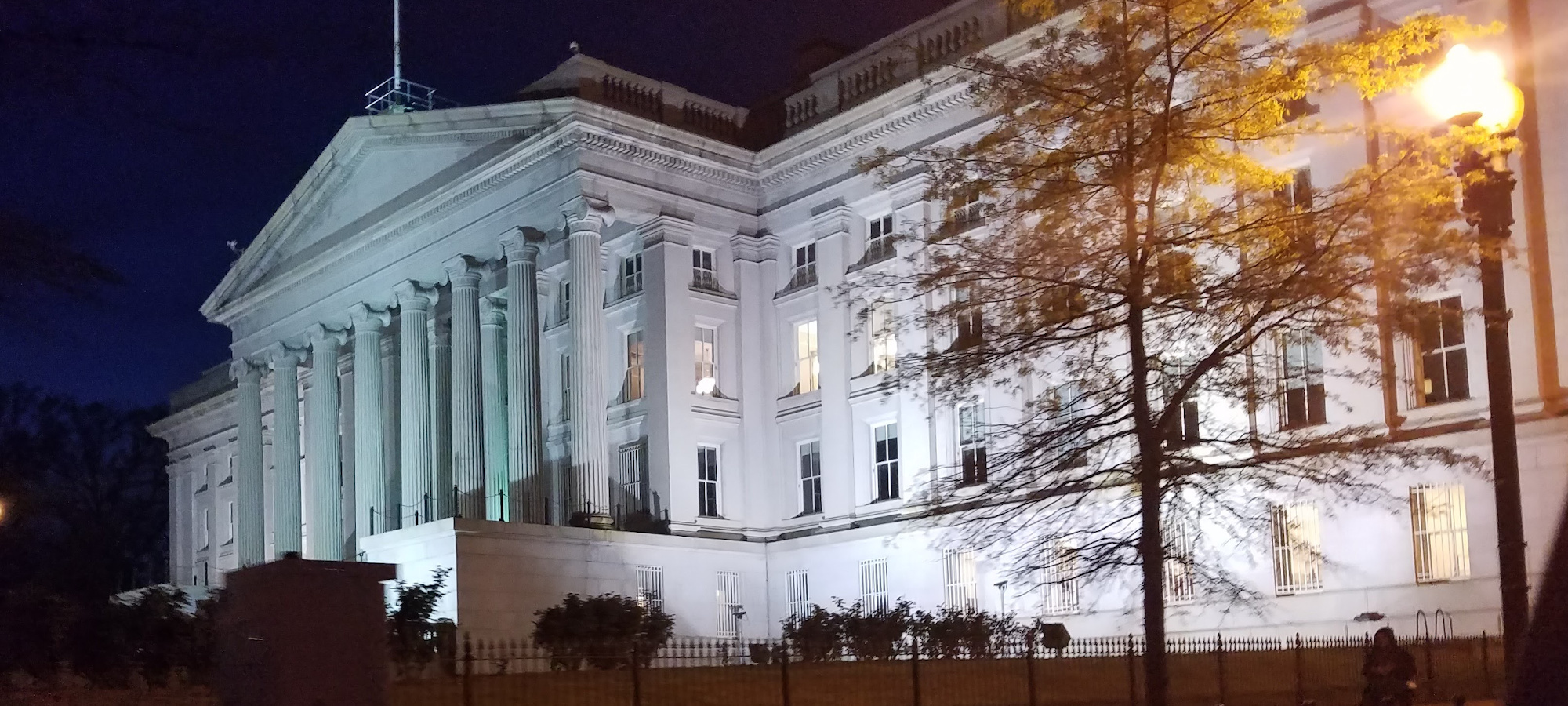

The oldest departmental building in Washington and has had a great impact on the design of other governmental buildings. At the time of its completion, it was one of the largest office buildings in the world. It served as a barracks for soldiers during the Civil War and as the temporary White House for President Andrew Johnson following the assassination of President Lincoln in 1865. The Treasury Building is unquestionably a monument of continuing architectural and historical significance. In acknowledgment of the building's significance, it was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1972.

https://soprema.us/projects/u-s-treasury-building-washington-dc

https://www.google.com/maps/place/US+Treasury+Department

https://www.google.com/maps/place/US+Treasury+Department

The Greek Revival style captured the spirit of the young republic. This building and the Patent Office, undertaken at the same time, are the most outstanding examples of Greek Revival civil architecture in the country. Not only were they the largest non-military buildings undertaken by the federal government in their own time, but they also influenced countless examples of civil architecture across the nation.

From 1800, the Treasury Department was housed in the first of George Hadfield's three brick Executive Offices, built between 1798 and 1799 on the site of the present north wing. The Treasury Office caught fire in 1801, 1814, and 1833, and it was not reconstructed after the third conflagration. Robert Mills, who had been in the capital since 1830, was asked to assess the fire, and by 1836, his plans for a new Treasury building were accepted by Andrew Jackson.

The Treasury Department building is the work of five major American architects:

- Robert Mills

- Thomas U. Walter

- Ammi B. Young

- Isaiah Rogers

- Alfred B. Mullett

Mills's design for the Treasury called for an E-shaped building opening west toward the White House, with a long classical facade on 15th Street, but only the east front and center wing were built under his supervision, from 1836 to 1842. The unusual vaulted structural system of the building and its monumental scale aroused suspicion in Congress, as well as some sharp professional jealousies among rival architects. In 1838, a bill was introduced in Congress to authorize the demolition of the half-completed structure. The architect presenting the case for demolition was Thomas U. Walter, Philadelphia's leading Greek Revival practitioner. Walter was appointed Architect of the Capitol in 1851, and he was authorized to prepare plans for extending the Treasury in 1855. His concept, which was carried through as others executed the work, established the ultimate rectangular layout, double courtyards, and portico facades.

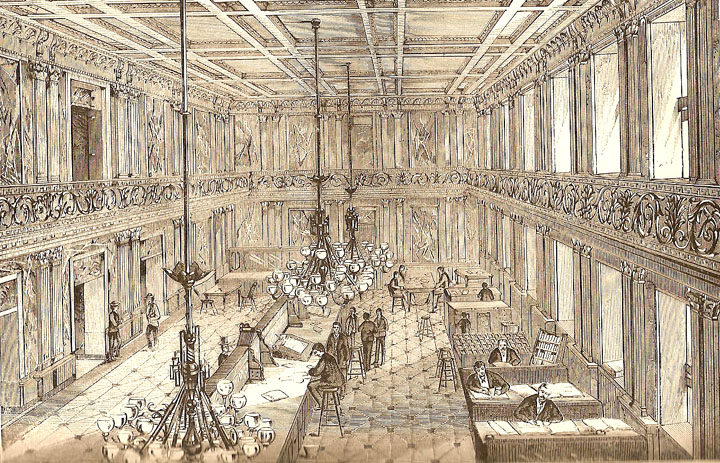

The south wing was built from 1855 to 1861 under the supervision of Ammi B. Young, appointed Supervising Architect of the Treasury in 1852. While Mills had been forced to use Aquia Creek sandstone, the extension was carried out in granite. The columns were monoliths, whereas Mills' had been built up in drums. Young was abruptly dismissed by Secretary Salmon P. Chase in 1862 and replaced by Isaiah Rogers, who remained in the job until 1865, supervising completion of the west wing (1855-64), addition of an attic floor on all the wings (1863-65), and preliminary planning for the north wing. Upon his resignation, Rogers was succeeded by his former subordinate Alfred B. Mullett, who completed the north wing between 1867 and 1869. This wing contains the elaborately decorated marble Banking Room, which was the setting for Ulysses Grant's first inaugural ball in 1869.

By the late 1890s, the need for additional office space led to the insertion of a large truss-roofed drafting room in the south courtyard, for use by the Supervising Architect of the Treasury. The poor quality of the building's original Aquia Creek sandstone led to the rebuilding of Mills' colonnade. Architects York and Sawyer added an attic story to the building between 1909 and 1910 and made other alterations through 1923.

Interior:

The Mills interiors are minimally decorated, their architectural character resulting from the masonry barrel-vaulted corridors, flanked by groin-vaulted offices. The elegantly curved, cantilevered marble staircases are a signature of his work. In contrast, the interiors of the three later wings rely much more on interior decoration for their architectural character. In these wings, Young, Rogers, and Mullett made extensive and imaginative use cast iron of and cast plaster decoration, including cast iron pilasters and friezes in the main corridors. Mullett's Cash Room is the most lavish space in the building, displaying seven varieties of marble in the paneled walls, and richly sculptural bronze railings for the balcony.

https://historicsites.dcpreservation.org/items/show/603?tour=1&index=15

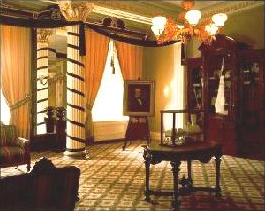

Restored, and historically significant, is the Salmon P. Chase suite, named after Lincoln's secretary of the Treasury who later became chief justice of the Supreme Court. One of Treasury's most elaborate mirrors is installed over the room's mantelpiece. It is believed to have been designed by J. Goldsborough Bruff, who worked in the Treasury architect's office; the fruits-and-vegetables theme symbolizes the abundance of America's agriculture.

Conservators stripped nearly a century's worth of paint to reveal two allegorical frescoes: a pastel-colored one called "Treasury," with a cornucopia of coins, and "Justice," a figure with a scale and sword, reflecting Chase's backgrounds in finance and law, and perhaps his forward-looking attitude (he is credited as the first person to hire women in the federal workforce, to replace men during the Civil War).

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/02/01/garden/01treasury.html

The assassination of Lincoln came at a critical time in our country's history, just one week after the surrender of the Confederate Army. The President's plans to reunite the country were interrupted on April 14, 1865 when John Wilkes Booth fired a fatal shot at Lincoln. The following morning Lincoln died, making his vice-president, Andrew Johnson, the seventeenth president of the United States.

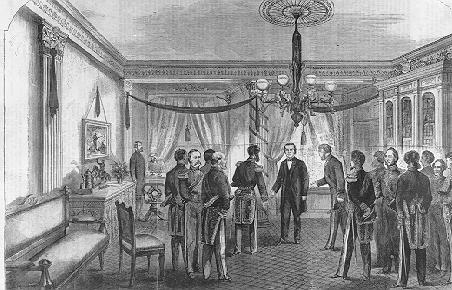

As a courtesy to Mary Todd Lincoln, Johnson delayed moving into the White House, allowing Mrs. Lincoln time to recover and plan her departure. In the meantime, Secretary of the TreasuryHugh McCulloch offered his recently decorated reception room for the President's official use. Here, within hours of Lincoln's death, Andrew Johnson held his first cabinet meeting in what would be his temporary executive office for the next six weeks.

https://home.treasury.gov/about/history/the-treasury-building/andrew-johnson-suite

Renovators at the Treasury Building made an unexpected discovery in 1985 behind the walls in the old office of the Treasurer. They had stumbled across the forgotten armored vault that used to guard the government's cash.

The old vault was designed in 1864 by Isaiah Rogers and employed a creative "burglar-proof" design. A double layer of large ballbearings were sandwiched between a metal housing - the theory was that an attacking drill bit would just penetrate one layer and get caught in the spinning the balls. In any case, a retinue of 20 guards used to guard the space to ensure that it never came to that.

According to Fortress of Finance, by 1881 the Rogers vault was crammed with $1 billion in securities, $500 million in bonds and several million in gold and silver coins.

In addition to gold and silver, the vault used to hold many other strange treasures including "paintings, prints and photographs, furniture, decorative arts, sculpture, and architectural fragments."

1909 Cash Room:

The Rogers vault was replaced by a larger cash room in 1909 under the Department's south plaza. The newer subterranean space had double-story shelving, similar to library stacks. According to the Washington Post, the only way to get in was "by way of a tiny hydraulic elevator, which is protected by an iron door, opening almost at the elbow of the chief of the division of issues, who keeps the key in his desk."

Contemporary newspaper articles fawned over an advanced-for-the-time alarm system. The walls of the room were lined with a dense mesh of wires that, if disturbed from the outside, would send an electronic alert to a nearby guard station. The alarm would also activate if the connection between the guard post and vault were interrupted. The alarm 'checked in' with the guard post every 15 minutes, 24 hours a day.

1935 Fort Knox

The government moved its gold and silver reserves in 1935, in order to conform "With the Treasury Department's policy of moving all large gold deposits away from cities exposed to enemy attack." The so called "deep storage" loot is now stored at Treasury facilities in Fort Knox, Denver, and West Point.

https://architectofthecapital.org/posts/2016/8/14/vault-room-under-the-treasury-department

The US Treasury Cash Room dates back to 1869, when it was the location for the transaction of the government's financial business. The Treasury needed a bank in the building, and so one was built — in the style of "a roofed version of an Italian palazzo, a traditional bank design throughout Europe." It features seven different types of marble, three big old chandeliers

It was a "banker's bank" but it also did things for private citizens, like cashing checks. New deliveries of coinage and paper currency would be brought there and stored in its vaults, millions of dollars' worth at a time.

The Cash Room closed in 1976 after it became clear that the costs of upkeep and running it were fast outpacing its actual usefulness.

https://tradepractices.wordpress.com/2012/07/03/us-treasury-cash-room

Before the Civil War on December 8, 1860, Secretary Howell Cobb wrote to President Buchanan:

I should no longer continue to be a member of your Cabinet. In the troubles of the country consequent upon the late Presidential election, the honor and safety of my State are involved... The evil has now passed beyond control, and must be met by each and all of us under our responsibility to God and our country.

Cobb left the Department of the Treasury in a state of disarray, with the South Wing extension unfurnished and the West Wing project completely halted, with slabs and columns of stone lining Pennsylvania Avenue.

It took seven Secretaries including Cobb, Thomas, Dix, Chase, Fessenden, and McCulloch and was led by four different architects, Walter, Young, Rogers, and Mullett to complete the West Wing expansion.

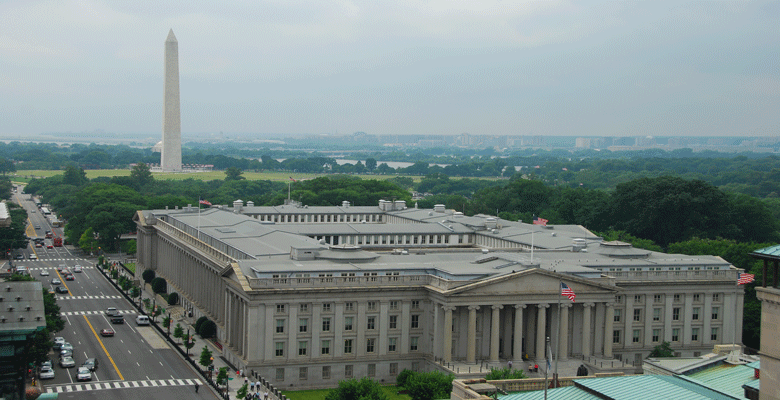

It fronts the White House:

As the capital city prepared for inevitable war, they feared that there was a conspiracy to seize the Treasury and the Capitol, thus attempting to establish the Confederate government in the hallowed halls of Union strongholds.

When Lincoln assumed the Presidency and the Civil War officially began in 1861, the Treasury building became so much more than a fortress of finance.

Between 1861 and 1865, the West Wing of the Treasury was completed, symbolizing the strength of the Union through turbulent times.

During this time, the Treasury Building served as not only a barricade and barracks for soldiers but a site of new innovation and the temporary White House for Johnson after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

Before Lincoln took office, it had been decided by General Winfield Scott and Charles P. Stone that the Treasury would be used as an army barricade because of its sheer size, resources, and newly built basement that could serve as the Presidential bunker

The building was prepared for war and served as a central barricade and living quarters for the Union soldiers attempting to protect Washington D.C. from the Confederate rebels

In January of 1862 due to an increase in business, the need for more space for office space, and room for Treasury Note manufacturing, thanks to the National Currency Act of July 1861 which authorized "greenback" issuance, Construction on the West Wing resumed.

When the National Currency Act was passed in July 1861, it allowed the federal government to issue paper money. These "greenbacks" were printed off-site and shipped to the Treasury where they had to be separated and individually signed by Treasury clerks, thus creating a factory-system. This method required secure supervision and large amounts of space in order to process notes valued over $250 million.

Why was the Treasury the fortress of major protection and not the White House? Its location, next to the White House, made the Treasury Department the perfect place to hold soldiers but General Scott made sure that it was so much more than that:

All else must be abandoned, if necessary, to occupy, strongly and effectively, the Executive Square, with the idea of finally holding only the Treasury building...and should it come to the defense of the Treasury building as a citadel, then the President and all the members of his Cabinet must take up their quarters with us in that building! They shall not be permitted to desert the Capital!

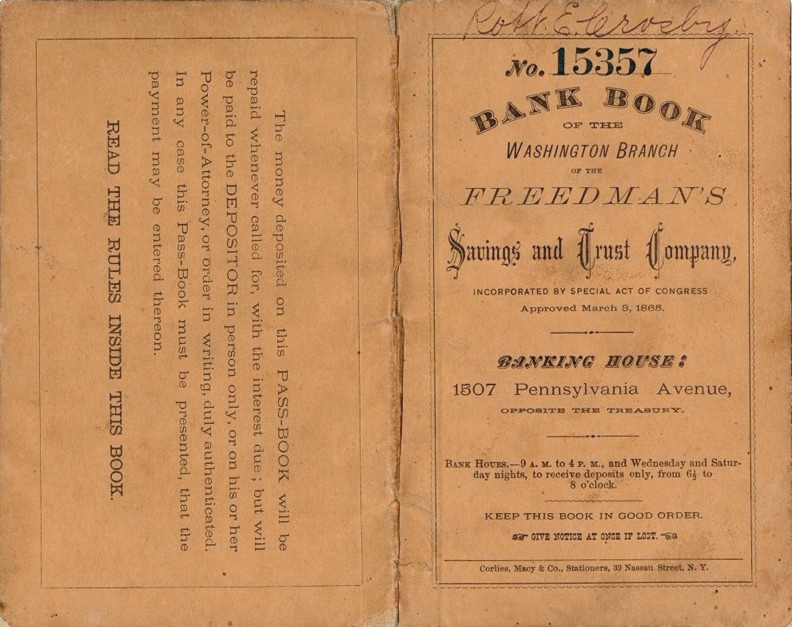

As the Civil War drew to a close, the United States Congress and President Lincoln recognized the need to aid newly freed black men and women in their transition to freedom. To support the land grants and other elements of the Freedman's Bureau Act, a Freedman's Bank was established to help newly freed Americans navigate their financial lives.

During it's existence, The Freedman's Bank maintained some 37 offices in 17 states, including the District of Columbia.

Seven years later, In June of 1872, the U.S. Congress voted to permanently close the Freedman's Bureau. The Bank however remained operational and in 1874 Frederick Douglass was asked to run the Freedman's Bank as its D.C. branch relocated to a new home across from the U.S. Department of Treasury, in a grand building.

When Douglass came on as the Bank's director however, he found rampant corruption within the Bank and risky investments across industries being made with depositor's savings. In a desperate attempt to stabilize the Bank, Douglass invested $10,000 of his personal funds, but sadly, later that year, in June of 1874 the Bank failed against the backdrop of the political forces that undermined Reconstruction. In the District alone over 3,000 depositors—both individuals and cultural institutions—lost their savings.

While the failure of the Freedman's Bank was tragic and left many African Americans with feelings of distrust of the American banking system, the records created by the bank are a rich source of documentation for black family research for the period immediately following the American Civil War. The records of twenty-nine branches of the Freedman's Savings Bank, including those of the Washington D.C. office, still survive today and are searchable at the National Archives.What make these records so important are the thousands of signature cards that contain personal data about the individual depositors.

In addition to the names and ages of depositors, the files can contain their places of birth, residence, and occupations; names of parents, spouses, children, brothers, and sisters; and in some cases, the names of former slave owners.

https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/freedmans-bank.html

Renamed:

On On January 7, 2016, the Treasury Annex Building was renamed The Freedman's Bank Building, in honor of the site where the Freedman's Saving Bank once stood.

The Department of Treasury moved into a porticoed Gregorian-style building, designed by George Hadfield in 1800 when the federal government moved from Philadelphia. The structure was destroyed by the British in 1814, but rebuilt by James Hobson. It was again burned, this time by arsonists in 1833, with only the fireproof wing left standing.

Three years later, on July 4, 1836, Congress authorized construction of a new East and Center Wings. The most architecturally impressive feature of the Mills design is the 341-foot long colonnade of thirty 36-foot tall columns each one carved out of a single block of granite.

History of the Department of the Treasury:

History of the Department of the Treasury:The second oldest department in the Federal government, the United States Department of the Treasury was created by the Congress on September 2, 1789. Besides fulfilling its responsibility of managing money, the Department has performed many other functions in the past. Examples of agencies that have sprung from earlier Treasury organizations include portions of the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Health & Human Services, Homeland Security, the Interior, and Justice, as well as the General Services Administration, the Office of Management and Budget and, in the Legislative Branch, the Government Accountability Office.

Currently, Treasury consists of twelve bureaus and components, as well as the Departmental Offices (previously titled "Office of the Secretary"), with a total of over 103,000 employees (FY 2017). The primary activities of the Department include: economic and fiscal policy development; international and domestic economic research; government accounting; cash and debt management; supervision of financial institutions; production of currency, coins and commemorative medals; assessment and collection of taxes; and, fostering interagency and global cooperation against domestic and international financial crimes, as well as internal auditing and investigative functions.

https://treasuryhistoricalassn.org/index.php/treasury-history-tours/treasury-department

https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/treasury-org-chart.png

Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade:

Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade:The history of taxation and regulatory control on the alcohol and tobacco industries is as old as our nation itself. Since 1789, the United States Treasury Department and its Bureaus have played an integral role in writing its history and in defining our nation's identity. The Department's work with the alcohol and tobacco industries has been carried out by numerous agencies under just as many names, but those individuals serving to uphold the government's interests share in more than two centuries of dedicated service to the American people.

Today, the Department's work with the alcohol and tobacco industries is carried out by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau. TTB was created in January of 2003, when the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms was extensively reorganized under the provisions of the Homeland Security Act of 2002. The Act called for the tax collection functions to remain with the Department of the Treasury, and TTB was born.

TTB's mission is simple... to collect alcohol, tobacco, firearms, and ammunition excise taxes; to ensure that these products are labeled, advertised, and marketed in accordance with the law; and to administer the laws and regulations in a manner that protects the consumer and the revenue, and promotes voluntary compliance from industry members. And while TTB is the newest bureau under the Department, the roots of its vision and mission date back to the creation of the Treasury Department and the first Federal taxes levied on distilled spirits in 1791.

As such, TTB builds upon a rich history, one that is marked with accomplishment and success. After all, it was a Treasury agency that collected the first source of tax income for our new Republic: an excise tax on distilled spirits. These taxes, as called for by Alexander Hamilton, paid off our nation's debt in the Revolutionary War. It was the Treasury Department that found itself in the middle of the Whiskey Rebellion, an event that would later come to stand as the first true test of our Federal government's legitimacy.

Later, Treasury collected taxes and issued stamps for alcohol and tobacco products in order to finance the Civil War. And during the early part of the twentieth century, the Treasury Department enforced the Eighteenth Amendment, and through the work of agents like Eliot Ness, leader of "The Untouchables," brought to justice those who used the illegal liquor industry to finance organized crime.

Today, TTB employs some 600 people across the country, including our Headquarters Offices in Washington, D.C., and the National Revenue Center in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Bureau of Engraving and Printing:

Bureau of Engraving and Printing:As its primary function, the BEP prints billions of dollars - referred to as Federal Reserve notes - each year for delivery to the Federal Reserve System. The Federal Reserve operates as the nation's central bank and serves to ensure that adequate amounts of currency and coin are in circulation. The BEP does not produce coins - all U.S. coinage is minted by the United States Mint. The BEP also advises other federal agencies on document security matters. In addition, the BEP processes claims for the redemption of mutilated currency. The BEP's research and development efforts focus on the continued use of automation in the production process and counterfeit deterrent technologies for use in security documents, especially United States currency.

The BEP had its foundations in 1862 with workers signing, separating, and trimming sheets of United States Notes in the Treasury building. Gradually, more and more work, including engraving and printing, was entrusted to the organization. Within a few years, the BEP was producing Fractional Currency, revenue stamps, government obligations, and other security documents for many federal agencies. In 1877, the BEP became the sole producer of all United States currency. The addition of postage stamp production to its workload in 1894 established the BEP as the nation's security printer, responding to the needs of the U.S. government in both times of peace and war. Today, the BEP no longer produces government obligations or postage stamps, but it still holds the honor of being the largest producer of government security documents with production facilities in Washington, DC, and in Fort Worth, Texas.

| History of U.S. Currency |

|---|

| https://moneyfactory.gov/uscurrency/history.html |

1690 Colonial Notes:The Massachusetts Bay Colony, one of the 13 original colonies, issues the first paper money to cover costs of military expeditions. The practice of issuing paper notes spread to the other colonies. |

1739 Franklin's Unique Counterfeit Deterrent:Benjamin Franklin's printing firm in Philadelphia prints colonial notes with nature prints--unique raised impressions of patterns cast from actual leaves. This process added an innovative and effective counterfeit deterrent to notes, not completely understood until centuries later. |

1775 Continental Currency:The Continental Congress issues paper currency to finance the Revolutionary War. Continental currency was denominated in Spanish milled dollars. Without solid backing and easily counterfeited, the notes quickly lost their value, giving rise to the phrase "not worth a Continental." |

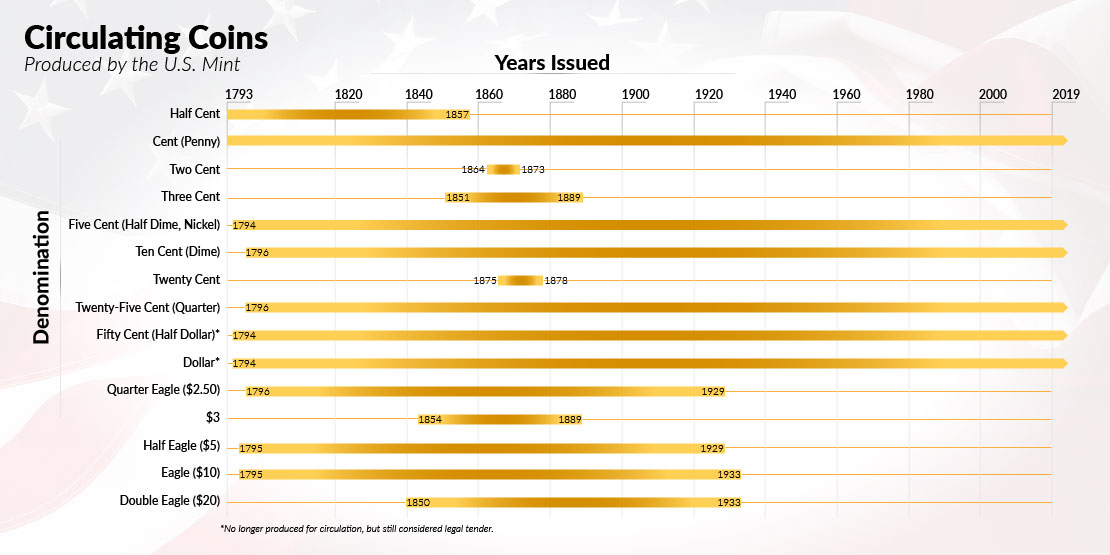

1792 Monetary System:The Coinage Act of 1792 creates the U.S. Mint and establishes a federal monetary system, sets denominations for coins, and specifies the value of each coin in gold, silver, or copper. |

1861 Greenbacks:The first general circulation of paper money by the federal government occurs. Pressed to finance the Civil War, Congress authorizes the U.S. Treasury to issue non-interest-bearing Demand Notes. All U.S. currency issued since 1861 remains valid and redeemable at full face value. |

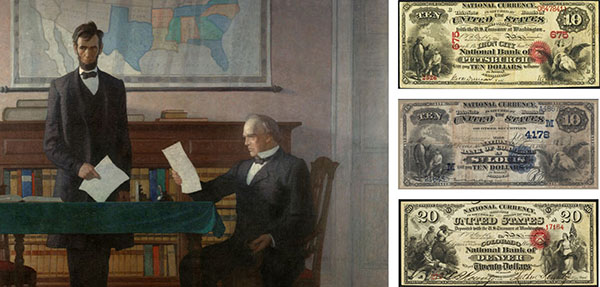

1861 First $10 Bills – Demand Notes:The first $10 notes are Demand Notes, issued in 1861 by the Treasury Department. A portrait of President Abraham Lincoln is included on the face of the notes. |

1862 Treasury Department Authorization:The Treasury Secretary is authorized to engrave and print notes at the Treasury Department; the design of which incorporates fine-line engraving, intricate geometric lathe work patterns, a Treasury seal, and engraved signatures to aid in counterfeit deterrence. |

1862 Spencer Clark:Spencer M. Clark, Chief Clerk in the Treasury Department's Bureau of Construction, obtains presses for the Treasury's Loan Branch for overprinting seals on notes. About the same time, Clark experiments with two hand-crank machines for trimming and separating. Later that year, Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase directs Clark to proceed with trials using steam-powered machines to trim, separate, and seal $1 and $2 United States Notes. |

1863 National Banknotes:Congress establishes a national banking system and authorizes the U.S. Treasury to oversee the issuance of National Banknotes. This system sets federal guidelines for chartering and regulating "national" banks and authorizes those banks to issue national currency secured by the purchase of United States bonds. These notes are printed by private companies and finished by the BEP until 1875, when the BEP begins printing the faces. |

1863 Fractional Currency:Fractional Currency notes, in denominations of 5, 10, 25, and 50 cents, are issued. This is the first currency produced entirely at the Treasury Department. |

1864 Spencer Clark :The 5-cent note of the second issue of Fractional Currency features the portrait of Spencer Clark, causing a public uproar. It is unclear how Clark's portrait ended up on the note, but in 1866, Congress prohibits the portrait or likeness of any living person on currency notes, bonds, or securities. |

1865 United States Secret Service :The United States Secret Service is established as a bureau of the Treasury for the purpose of deterring counterfeiters whose activities are destroying the public's confidence in the nation's currency. The Secret Service is now part of the Department of Homeland Security. |

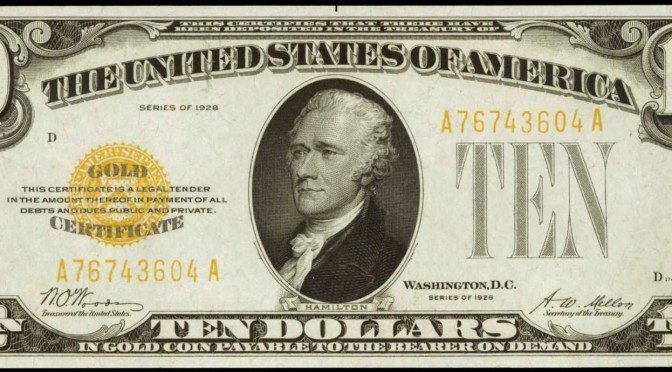

1865 Gold Certificates:Gold Certificates, backed by gold held by the Treasury, are first issued. Along with Fractional Currency, Gold Certificates are one of the first currency issues produced entirely by the BEP. |

1866 Revenue Stamps:The BEP begins producing revenue stamps to be placed on boxes of imported cigars. |

1869 United States Notes:The BEP begins engraving and printing the faces and seals of United States Notes, Series 1869. Prior to this time, United States Notes were produced by private banknote companies and then sent to the BEP for sealing, trimming, and cutting. |

1874 Bureau of Engraving and Printing:For the first time, Congress allocates money specifically to a "Bureau of Engraving and Printing" for fiscal year 1875. |

1876 All Revenue Stamps:Congress passes an appropriation bill that directs the Internal Revenue Service to procure stamps engraved and printed at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing – provided costs do not exceed that of private firms. As a result, the BEP begins producing almost all revenue stamps in fiscal year 1878. |

1877 All Currency:The BEP begins printing all United States currency. |

1878 Silver Certificates:Silver Certificates are first issued. Backed by silver held by the Treasury, the certificates are authorized by legislation directing an increase in the purchase and coinage of silver. |

1880 First Facility:The first building constructed specifically for BEP operations is completed at the corner of 14th Street and B Street (Independence Avenue). |

1890 Treasury Coin Notes:Treasury Notes, also known as Treasury Coin Notes, are first issued as part of legislation requiring the Treasury Secretary to increase government purchases of silver bullion. |

1894 Postage Stamps:The BEP begins printing postage stamps. The first BEP-printed stamp issued is the 6 cent President Garfield. |

1900 Postage Stamps:The first issue of postage stamps in small booklets is produced. |

1905 Paper Currency with Background Color:The last United States paper money printed with background color is the $20 Gold Certificate, Series 1905, which had a golden tint and a red seal and serial number. |

1912 Offset Printing:Offset printing is first used in the BEP for the production of checks, certificates, and other miscellaneous items. |

1913 Federal Reserve Act:The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 establishes the Federal Reserve as the nation's central bank and provides for a national banking system that is more responsive to the fluctuating financial needs of the country. Federal Reserve Bank Notes are authorized by the Federal Reserve Act and used as a form of emergency currency in the early twentieth century. The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System then issues new notes called Federal Reserve notes. |

1914 The first $10 Federal Reserve Notes:The first $10 Federal Reserve notes are issued. These notes are larger than today's notes and feature a portrait of President Andrew Jackson on the face. |

1914 New DC Facility:The BEP moves into a new, larger facility, later known as the "main" building. |

1929 Federal Reserve Note Standardized Design:The first sweeping change to affect the appearance of all paper money occurs in 1929. In an effort to lower manufacturing costs, all Federal Reserve notes are made about 30 percent smaller. The reduced size enables the BEP to convert from eight to 12 notes per sheet. In addition, standardized designs are instituted for each denomination across all classes of currency, decreasing the number of different designs in circulation. This standardization makes it easier for the public to distinguish between genuine and counterfeit notes. |

1938 Annex Building:BEP operations begin in the "annex" building. The building is officially dedicated in November, 1938. |

1939 Food Stamps:The BEP begins printing Food Order and Surplus Food Order stamps. The Cotton Order and Surplus Cotton Order stamps follow in 1940. The stamps encourage consumption of surplus farm commodities while providing assistance to low-income consumers. |

1942 Hawaii Overprints:The BEP receives an order for special $1, $5, $10, and $20 notes overprinted with the word "Hawaii." The overprinted notes replace regular currency in Hawaii. In the event of enemy occupation of the islands, the overprinted currency can be declared worthless. |

1943 Allied Military Currency:The War Department places an order for Allied Military Currency (AMC). The first AMCs are used by Allied forces in Italy. Production begins in July, 1943. |

1946 Military Payment Certificates:The BEP begins work on Military Payment Certificates for use by U.S. troops. |

1951 Congressional Appropriations:The BEP begins operating on a reimbursable basis in accordance with a legislative mandate to convert to business-type accounting methods. As a result, annual Congressional appropriations cease. |

1952 18-Subject Sheets:The BEP begins conversion from 12- to 18-subject sheets in currency production. The use of larger sheets is made possible by new non-offsetting ink. By reducing wetting and drying operations, distortion of paper is decreased. By September 1953, all currency is produced from 18-subject plates. |

1957 In God We Trust:Following a 1955 law that requires "In God We Trust" on all currency, the motto first appears on paper money on series 1957 $1 silver certificates, then on 1963 series Federal Reserve notes. |

1957 32-Subject Sheets:The BEP begins producing currency on high-speed rotary presses that print notes via the dry intaglio process. Paper distortion caused by wetting is now completely eliminated and sheet sizes increase from 18- to 32-subjects. The first notes printed by this process are the series 1957 silver certificates. |

1968 Barr Notes:Joseph W. Barr served as Secretary of the Treasury from December 21, 1968 to January 20, 1969. There are fewer notes bearing his facsimile signature than notes imprinted with signatures of other Secretaries of the Treasury because of his short tenure in that office. |

1969 High-Denomination Notes:The Treasury Secretary announces that currency in denominations larger than $100 will no longer be issued. Last printed in 1945, the high-denomination notes had been used mainly by banking institutions, but advances in bank transfer technologies preclude their further use. |

1976 $2 Federal Reserve Note:The $2 Federal Reserve note is re-introduced on the 233rd anniversary of Thomas Jefferson's birth. Issuance of the $2 United States Note had been halted in 1966 as United States Notes were phased out of existence. |

1990 Security Thread and Microprinting:A security thread and microprinting are introduced to deter counterfeiting by advanced copiers and printers. The features first appear in Series 1990 $100 notes. By Series 1993, the features appeared on all denominations except $1 and $2 notes. |

1990 Western Currency Facility:The BEP's Western Currency Facility in Fort Worth, Texas begins producing currency. It is the first government facility outside Washington, DC to print United States paper money. The facility is intended to better serve the currency needs of the western half of the nation and to act as a contingency operation in case of emergencies at the DC facility. |

1996 Currency Redesign:In the first significant design change in 67 years, United States currency is redesigned to incorporate a series of new counterfeit deterrents. The new notes are issued beginning with the $100 note in 1996, followed by the $50 in 1997, the $20 in 1998, and the $10 and $5 notes in 2000. |

2003 Redesigned $20 Note:For the first time since the Series 1905 $20 Gold Certificate, the new currency features subtle background colors, beginning with the redesigned $20 note on October 9, 2003. The redesigned $20 note features subtle background colors of green, peach and blue, as well as images of the American eagle. |

2004 Redesigned $50 Note:The currency redesigns continue with the $50 note, issued on September 28, 2004. Similar to the redesigned $20 note, the redesigned $50 note features subtle background colors and highlights historical symbols of Americana. Specific to the $50 note are background colors of blue and red, and images of a waving American flag and a small metallic silver-blue star. |

2005 Final Postage Stamp Run:The BEP produces its final run of postage stamps, printing the 37-cent Flag on the Andreotti gravure press. |

2006 Redesigned $10 Note:A redesigned Series 2004A $10 note is issued on March 2, 2006. The A in the series designation indicates a change in some feature of the note, in this case, a change in the Treasurer's signature. Like the redesigned $20 and $50 notes, the redesigned $10 note features subtle shades of color and symbols of freedom. Specific to the $10 note are background colors of orange, yellow and red, and images of the Statue of Liberty's torch and the words, We the People, from the United States Constitution. |

2008 Redesigned $5 Note:A redesigned Series 2006 $5 note is issued on March 13, 2008. The redesigned $5 note retains two of the most important security features first introduced in the 1990s: the watermark and embedded security thread. |

2013 Redesigned $100 Note:On October 8, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System issues the redesigned $100 note. Complete with advanced technology to combat counterfeiting, the new design for the $100 note retains the traditional look of U.S. currency. |

2014 50-Subject Printing:On February 14, the BEP ushers in a new era by completing its first $1 note 50-subject production order. Fifty-subject and 32-subject notes are distinguishable by one minor technical change. On a 50-subject produced note, the letter and number of the alpha numeric note-position identifier, is the same font size and smaller than the alpha letter of the 32-subject note. In comparison, on the 32-subject note, the number is a smaller font size compared to the letter. |

Bureau of the Fiscal Service:

Bureau of the Fiscal Service:Right before World War II, in 1939, President Franklin Roosevelt began a reorganization of the executive department. The president consolidated all Treasury financing activities into a "Fiscal Service" under the direction of a fiscal assistant secretary.

These activities included accounts, deposits, bookkeeping, warrants, loans, currency, disbursements, surety bonds, savings bonds, and the public debt.

By 1940, the Fiscal Service consisted of the Bureau of Accounts, the Bureau of the Public Debt, and the Office of the Treasurer—all under the direction of the fiscal assistant secretary.

A 1974 reorganization of the Fiscal Service created the Bureau of Government Financial Operations, which consolidated most of the functions of the Office of the Treasurer.

In 1984, the Bureau of Government Financial Operations was renamed the Financial Management Service (FMS). The new name reflected Treasury's aim to achieve greater efficiency and economy in government financial management.

During this time, the Bureau of the Public Debt (BPD) continued to track, account for, and manage the various elements of the public debt structure first established by George Washington's Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton.

On October 7, 2012, Treasury Secretary, Timothy Geithner issued Treasury Order 136-01 [ https://home.treasury.gov/about/general-information/orders-and-directives/treasury-order-136-01 ] creating the Bureau of the Fiscal Service, consolidating the operations of the Bureau of the Public Debt and the Financial Management Service.

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network:

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network:FinCEN is a bureau of the U.S. Department of the Treasury. The Director of FinCEN is appointed by the Secretary of the Treasury and reports to the Treasury Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence. FinCEN's mission is to safeguard the financial system from illicit use and combat money laundering and promote national security through the collection, analysis, and dissemination of financial intelligence and strategic use of financial authorities.

FinCEN carries out its mission by receiving and maintaining financial transactions data; analyzing and disseminating that data for law enforcement purposes; and building global cooperation with counterpart organizations in other countries and with international bodies.

FinCEN exercises regulatory functions primarily under the Currency and Financial Transactions Reporting Act of 1970, as amended by Title III of the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 and other legislation, which legislative framework is commonly referred to as the "Bank Secrecy Act" (BSA).

The basic concept underlying FinCEN's core activities is "follow the money." The primary motive of criminals is financial gain, and they leave financial trails as they try to launder the proceeds of crimes or attempt to spend their ill-gotten profits. FinCEN partners with law enforcement at all levels of government and supports the nation's foreign policy and national security objectives. Law enforcement agencies successfully use similar techniques, including searching information collected by FinCEN from the financial industry, to investigate and hold accountable a broad range of criminals, including perpetrators of fraud, tax evaders, and narcotics traffickers. More recently, the techniques used to follow money trails also have been applied to investigating and disrupting terrorist groups, which often depend on financial and other support networks.

FinCEN's insignia has FinCEN spelled out in binary code

Internal Revenue Service:

Internal Revenue Service:

Four primary IRS Divisions:

- Wage and Investment

- Large Business and International

- Small Business/Self-Employed

- Tax-Exempt and Government Entities

Other principal offices:

- Office of Chief Counsel

- Criminal Investigation

- Appeals

- Return Preparer Office

- Office of Professional Responsibility (OPR)

- Communications and Liaison

- Whistleblower Office

- Privacy, Governmental Liaison and Disclosure

- Equity, Diversity and Inclusion

- Procurement

https://www.irs.gov/about-irs/at-a-glance-irs-divisions-and-principal-offices

| IRS History Timeline: |

|---|

| https://www.irs.gov/irs-history-timeline |

1787 - 1789 Evolution of Taxation:On February 21, 1787, Congress approved a Constitutional Convention to revise the Articles of Confederation: "... the Congress shall have the power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excesses, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States." On September 2, 1789, Congress established the Department of the Treasury and appointed Alexander Hamilton as the first Secretary. |

1794 The Whiskey Rebellion:1794 saw the first outright challenge to the U.S. government's revenue laws when a federal court summoned 75 distillers in western Pennsylvania to appear in court and explain why they shouldn't be arrested for whiskey tax evasion. The Whiskey Rebellion set up a clash between citizens and federal officers. The federal government prevailed, but at a cost of $1.5 million to American taxpayers. |

1812 - 1817 The War of 1812:To pay for the War of 1812, Congress passed new internal taxes on refined sugar, carriages, distillers and auction sales and reinstated the Commissioner of the Revenue to collect them. On August 24, 1814, the British burned the Treasury building in Washington, D.C. On December 23, 1817, Congress repealed these and all remaining internal taxes and abolished the position of the Commissioner of the Revenue and all offices to collect them |

1836 - 1842 The Treasury Gets a New Home:Construction began on a new Treasury building in 1836. The first segment opened in 1842. |

1862 Civil War Expenses:On July 1, 1862, President Lincoln signed the second revenue measure of the Civil War into law. This law levied internal taxes and established a permanent internal tax system. Congress established the Office of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue under the Department of the Treasury. On July 17, 1862, George S. Boutwell became its first commissioner. |

1863 - 1864 Property Seizures and Tax Refunds:In its first year, 1863, the Office of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue collected $39.1 million. The Revenue Act of June 30, 1864, authorized the Commissioner of Internal Revenue to compromise all suits "relating to internal revenue," to abate outstanding assessments and to refund taxes subject to current regulations |

1867 State-of-the-Art Technology:In February 1867, the Secretary of the Treasury adopted a hydrometer to establish a uniform system to inspect and gauge alcoholic spirits subject to tax. The March 1, 1867 Revenue Act authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to adopt, procure and prescribe these and other weighing and gauging instruments to prevent and detect fraud by spirit distillers. |

1870 Personal Privacy:Representative (later president) James Garfield of Ohio spearheaded an effort to make tax information private. On April 5, 1870, IRS Commissioner Delano forbade tax assessors from furnishing lists of taxpayers for publication. On July 14, 1870, Congress passed a revenue act stating, "no collector ... shall permit to be published in any manner such income returns or any part thereof, except such general statistics ..." |

1913 First Federal Income Tax:On February 25, 1913, the 16th Amendment officially became part of the Constitution, granting Congress constitutional authority to levy taxes on corporate and individual income. The Bureau of Internal Revenue established a Personal Income Tax Division and Correspondence Unit to answer a flood of questions about its enforcement, and a special division within General Counsel to prepare opinions interpreting internal revenue laws. |

1914 Form 1040:On January 5, 1914, the Treasury Department unveiled the four-page form (including instructions) for the new income tax. The form was numbered 1040 in the ordinary stream of numbering forms in sequential order. In the first year, no money was to be returned with the forms. Instead, each taxpayer's calculations were verified by field agents, who sent out bills on June 1. Tax payments were due by June 30 |

1917 Public Awareness:In 1917, the Internal Revenue Bureau launched a special nationwide public education program to help citizens understand the new tax burden. The campaign tried to popularize war taxes by emphasizing the needs of the country and appealing to national pride and patriotism. "Four Minute Men" fanned out across the nation, preaching the importance of paying taxes promptly and fully. |

1919 Prohibition:Congress passed the National Prohibition Enforcement Act on October 27, 1919. It prohibited the manufacture, sale, and use of intoxicating beverages. It also designated the Bureau of Internal Revenue as the enforcement agency. The Bureau hired and trained hundreds of prohibition agents to enforce the law and created a new intelligence unit to uncover corrupt prohibition agents and bootleggers |

1930 Bureau of Internal Revenue Gets New Home:On June 1, 1930, the main section of the new Internal Revenue building opened, 16 months ahead of schedule and with a total construction cost of just over $6 million. In addition to a state-of-the-art fire alarm system, it contained 1,400 telephones and a synchronized system of 861 clocks, the largest system of its kind at the time. |

1931 Al Capone:American gangster Alphonse "Al" Capone attained fame during the Prohibition era by raking in millions of dollars through bootlegging and other illicit activities. In 1931, an IRS Intelligence Unit investigation led to his indictment on federal income tax evasion and violations of the Volstead Act. He pled guilty, was convicted, and sentenced to 11 years in federal prison, a $50,000 fine, and ordered to pay $215,000 plus interest on back taxes. |

1935 Payroll Withholding:On August 14, 1935, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act. Employees originally paid one percent of the first $3,000 of their salaries to finance the benefits. The law required a new system of tax withholding, which the Bureau of Internal Revenue had to collect and turn over to the Social Security Trust Fund. It also created an unemployment compensation program and laid the foundation for modern payroll withholding |

1942 Victory Tax:The Roosevelt administration hoped to pay for at least half the cost of World War II by increased taxation. The 1942 Revenue Act sharply increased most existing taxes, introduced the Victory tax (a 5 percent surcharge on all net income over $624 with a postwar credit), lowered exemptions and began provisions for medical and dental expenses and investors' expense deductions. Still, taxes only funded 43 percent of the war's cost, 7 percent short of the goal. |

1948 -1950 Early Tax Collection Modernization:In 1948, the Bureau introduced punch-card equipment to process notices. They also introduced photocopying to reduce the typing workload and relieve a typist and stenographer shortage. In 1949, the IRS introduced electric typewriters, continuous forms, dual-roller platens and posting machines to more efficiently process income tax returns. By 1950, the Bureau introduced computers for tabulation. |

1953 Internal Revenue Service Created:In 1952, President Harry S. Truman called for a comprehensive reorganization of the Bureau of Internal Revenue. The agency officially became the Internal Revenue Service on July 9, 1953. |

1950 - Present Taxpayer Communication and Support:During the 1950s, the Service primarily interacted with taxpayers through written and print communication using the U.S. Postal Service and walk-in offices. Walk-in offices, or Tax Assistance Centers (TAC), continue to help taxpayers today. |

1953 - 1959 Public Outreach:In 1953, the IRS began the "Teaching Taxes" program by mailing a tax kit with teaching text, enlarged copies of tax return forms and regular return forms to 30,000 junior and senior high school principals. By 1959, the IRS offered public service announcements to television and radio stations throughout the entire year, not just during filing season. |

1959 - 1962 IRS Modernizes Data Processing:In 1959, Congress and the Secretary of the Treasury approved IRS plans to install a nationwide automatic data processing system. By January 1962, automated data processing entered full operation, processing up to 680,000 characters per second |

1961 President Kennedy Visits IRS:On May 1, 1961, President John F. Kennedy attended the Joint Conference of Regional Commissioners and District Directors of the IRS. The only U.S. president to visit IRS headquarters, President Kennedy praised the Service for pursuing fair taxation in the promotion of national interest. |

1962 Tingle Table Invented:For over 50 years, Tingle Tables have saved taxpayers millions of dollars by reducing the time it takes IRS employees to sort through individual paper-filed returns. In 1962, James Tingle invented the table while working in an IRS Service Center. Mr. Tingle built the prototype in his backyard. Still in use today, over 15 million tax returns flowed through the tables during the 2019 tax filing season. |

1966 - 1967 Taxpayer Service:The toll-free telephone network system, piloted in 1966, eventually allowed the IRS to handle most taxpayer inquiries by phone. On January 1, 1967, the IRS launched a nationwide, automated federal tax system. That same year, the IRS established a long-range study to determine automated data processing requirements through 1970 and beyond. |

1972 - Present Reaching More Taxpayers:In 1972, the IRS began to offer tax information in Spanish. Over time, translations expanded to include additional languages in print and on IRS.gov. In 1976, the Service offered toll-free telephone and teletypewriter service to the deaf and hard of hearing. Today, the IRS provides support through social media channels, relay services, American Sign Language YouTube videos, and at Volunteer Individual Tax Assistance Centers. |

1978 Faster, More Accurate Service:In 1978 the IRS installed a Remittance Processing System (RPS) and an Omnisort mail sorting system in all service centers. The system automated the sorting and opening of incoming tax returns at a rate of 22,000 pieces of mail per hour with a 98 percent accuracy rate. In contrast, the top speed of the manual sort process it replaced was 1,200 pieces per hour. |

1986 Tax Reform Act of 1986:U.S. Congress passed the Tax Reform Act to "simplify the income tax code." The Service marked a pivotal change in the way it interacted with taxpayers by beginning the progression from paper-based filing to electronic filing. |

1988 Service Design:In 1978, the IRS studied the economic, social and behavioral factors that impact taxpayer compliance. In 1986, the IRS established an artificial intelligence laboratory as part of an initiative to explore potential applications of new technologies to tax processing. In 1988, the IRS revised its "Understanding Taxes" program for high school students to include computer software and video programs in the instructional materials. |

1988 Taxpayer Rights:In 1988, the IRS published Publication 1, Your Rights as a Taxpayer, which required the IRS to fully inform taxpayers of their rights as a taxpayer and the processes for examination, appeal, collection, and refunds. |

1991 Electronic Filing:The IRS started electronic filing to lower operating costs and paper use. The Service anticipated over 90% of 150 million individual returns would be filed electronically for the 2019 tax-filing season. |

1994 IRS Bulletin Board System:The National Technical Information Service (NTIS) established FedWorld in 1992 to serve as the online locator service for an extensive inventory of information distributed by the federal government. Two years later in 1994, NTIS launched a Bulletin Board System (BBS) to support the IRS, giving the Service the ability to provide forms and publications online. |

1996 - 2018 Digital Daily:The Digital Daily was the first presence of the IRS on the World Wide Web. It had a warm and humorous tone, and a design that resembled a newspaper. The site grew and evolved into IRS.gov, which had more than 609 million visits in 2018. |

1998 Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998:The IRS Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998 prompted the most comprehensive reorganization and modernization of the IRS in nearly half a century. The IRS reorganized itself in 2000 to closely resemble the private sector, creating four major business divisions, each aligned to a group of taxpayers with similar needs. |

2001 - 2007 Digital Tools for Taxpayers:The IRS leaned into digital innovation, launching multiple tools:

|

2002 - 2013 Online Payments:To keep up with digital demand, the IRS introduced two applications that allowed taxpayers to pay their bills online.

|

2004 - 2008 Digital Tools for Tax Professionals:In a continued effort to move toward a paperless filing process, the IRS launched digital solutions for tax professionals.

|

2010 IRS Student Aid Tool:The Department of Education and the IRS collaborated to build a tool that enabled students and parents to transfer tax information from the IRS directly to their Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) online application, streamlining the student aid application experience. |

2011-2015 IRS Goes Mobile:As taxpayers moved toward mobile devices, the IRS developed applications to meet demand. In January 2011, the IRS launched its first native mobile application, IRS2Go. The app initially allowed taxpayers to check the status of their refunds and returns from their mobile devices. Subsequent updates let users access free tax preparation assistance, link to IRS news and use the app in Spanish. |

2014 Taxpayer Bill of Rights:In 2014, Commissioner John Koskinen and Taxpayer Advocate Nina E. Olson released an enhanced Taxpayer Bill of Rights. Written to be clear, understandable and accessible for both taxpayers and IRS employees, the updated document grouped the dozens of existing rights in the tax code into ten fundamental rights. The Taxpayer Bill of Rights is displayed in IRS offices across the country as a reminder that "respecting taxpayer rights continues to be a top priority for IRS employees." |

2016 Tax Design Challenge:IRS hosted its first crowdsourcing competition that encouraged innovative ideas for the taxpayer experience of the future. Of 48 submissions, winners from California, Minnesota and Washington, D.C., were among those selected in categories covering:

|

2016 Online Account:In November 2016, the IRS launched Online Account, a self-service application that allows taxpayers to check the amount they owe, see their payment history for the last two years, view a snapshot of their most recently filed tax return and link to payment options or full transcripts. |

2017 IRS.gov Redesigned:In August 2017, the IRS.gov team launched a major refresh of the website. The new site was designed to be accessible for people with disabilities, viewable on mobile devices and organized for taxpayers to quickly find what they need. |

2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act:On December 22, 2017, President Donald J. Trump signed into law H.R. 1, known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the most significant piece of tax reform legislation in decades. Today, the IRS continues its mission to provide America's taxpayers with top quality service by helping them understand and meet their tax responsibilities and enforce the law with integrity and fairness to all. |

2018 IRS Social Media:As part of its mission to help taxpayers understand and meet their tax responsibilities, the IRS added Instagram to its social media portfolio in late 2018. The @IRSnews account brings new audiences closer to tax topics that affect all taxpayers. The Service also has an established presence on:

|

2018 New 1040:As part of a larger effort to help taxpayers, the Internal Revenue Service streamlined the Form 1040 into a shorter, simpler form. In December 2018, the IRS released the redesigned Form 1040 and six accompanying schedules for taxpayers with more complicated returns. This new Form 1040 retired the use of Form 1040-A and Form 1040-EZ for tax year 2018. |

2019 Criminal Investigation Centennial:In 1919, the Treasury Secretary asked the IRS Commissioner to form a criminal investigation unit to go after tax cheats and other criminals. 100 years later, Criminal Investigation (CI) special agents continue to bring down the most notorious criminals. CI remains the only law enforcement agency with the authority to investigate tax crimes—and has earned the reputation as the premier financial investigation unit in the world. |

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency:

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency:The OCC ensures that national banks and federal savings associations operate in a safe and sound manner, provide fair access to financial services, treat customers fairly, and comply with applicable laws and regulations. It supervises nearly 1,200 national banks, federal savings associations, and federal branches and agencies of foreign banks that serve consumers, businesses, and communities across the United States and conducts approximately 70 percent of banking activity in the country. These banks range from community banks serving local neighborhood needs to the nation's largest most internationally active banks.

The Comptroller also serves as a Director of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and a member of the Financial Stability Oversight Council and the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council.

February 25, 1863:

President Lincoln signed the National Currency Act into law, creating the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and charging it with responsibility for organizing and administering a system of nationally chartered banks and a uniform national currency.

President Abraham Lincoln recognized that the United States' fragmented banking and monetary system needed tighter structure and order.

President Lincoln recognized that unreliable paper money and inadequate credit was problematic. Along with his Treasury Secretary, Salmon P. Chase, he conceived the national banking system and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency to regulate and supervise it.

Through the National Bank Act, Congress sought to achieve both short- and long-term goals. One crucial objective was to generate cash desperately needed to finance and fight the Civil War. After prospective national bank organizers submitted a business plan and had it approved by the OCC, they were required to purchase interest-bearing U.S. government bonds in an amount equal to one-third of their paid-in capital. Millions of much-needed dollars flowed into the Treasury in this manner.

But the national banking system was also designed to achieve longer term economic goals. Under the new system, the purchased bonds were to be deposited with the Treasury, where they were held as security for a new kind of paper money: national currency. Bearing the name of the issuing national bank and the signatures of its officers, these notes were otherwise identical in design, size, and coloration. Anyone holding a national bank note could present it for redemption in, gold or silver coin, at the issuing bank or at reserve banks around the country. If, for whatever reason, the issuing bank was unable to meet the demand for cash redemption, the system was set up so that the government could sell the bank's bonds and pay off the noteholders directly.

Once accepting and holding national currency became essentially risk-free, it gained in public confidence and circulated throughout the nation. This represented a marked improvement over the pre-Civil War money supply, which had involved thousands of different varieties of paper money issued by local banks, rampant counterfeiting, chronic uncertainty about the value of paper money, and, as a result, difficulty conducting private business. Through the more orderly national money and banking system, Congress sought to promote economic growth and prosperity and a stronger sense of American nationalism.

Shortly after the turn of the 20th century, the country adopted a new currency system based on Federal Reserve notes, which were obligations of the government rather than individual banks. With that change, national currency faded in importance, and the OCC's mission focused increasingly on the safety and soundness of national banks.

U.S. Mint:

U.S. Mint:On April 2, 1792, Congress passed the Coinage Act, establishing the first national mint in the United States. During the Colonial Period, monetary transactions were handled using foreign or colonial currency, livestock, or produce. After the Revolutionary War, the U.S. was governed by the Articles of Confederation, which authorized states to mint their own coins.

In 1788, the Constitution was ratified by a majority of states and discussions soon began about the need for a national mint. Congress chose Philadelphia, what was then the nation's capital, as the site of the first Mint. It was the first federal building erected under the Constitution. Coin production began immediately. The Act specified the following coinage denominations:

- In copper: half cent and cent

- In silver: half dime, dime, quarter, half dollar, and dollar

- In gold: quarter eagle ($2.50), half eagle ($5), and eagle ($10)

In March 1793, the Mint delivered its first circulating coins: 11,178 copper cents.

In 1795, the Mint became the first federal agency to employ women: Sarah Waldrake and Rachael Summers were hired as adjusters

Southern Branch Mints:

In the early 1800s, America experienced its first two gold rushes: first in North Carolina and then in Georgia. Demand on the Philadelphia Mint to melt, refine, and produce coins from this gold pushed the Mint to its limits. In 1835, Congress passed legislation to establish three new branch Mints located in Charlotte, NC; Dahlonega, GA; and New Orleans, LA.

In 1861 at the beginning of the Civil War, the Confederacy gained control of these three facilities, sporadically making Confederate coinage before converting all of them to assay offices. The U.S. regained possession of the facilities in 1862. Dahlonega never reopened, and Charlotte opened briefly in the 1870s as an assay office. The New Orleans Mint opened in 1879 to produce silver and gold coins until it stopped coining operations in 1909.

Mint Expands West:

In 1849, the California Gold Rush brought a flood of people west for the chance to get rich. Transporting the gold east all the way to the Philadelphia Mint was time-consuming and fraught with risk. In 1854, a branch Mint opened in San Francisco to convert the miners' gold into coins. By the end of that year, the San Francisco Mint produced $4,084,207 in gold coins.

Denver:

Gold fever spread to Colorado in 1858, bringing hundreds of people to settle around the new city of Denver. In 1862, Congress approved a branch Mint in Denver and bought the building of Clark, Gruber and Company, a private mint. The following year, the Denver facility opened as an assay office for miners to bring gold to be melted, assayed, and cast into bars. It didn't produce any gold coins, as was originally intended. In 1895, Congress converted the Denver facility back to a Mint, and in 1906 it produced its first gold and silver coins.

Carson City:

The country's largest silver strike, referred to as the Comstock Lode, started in Nevada in 1859. Congress authorized a branch Mint in nearby Carson City. The Carson City Mint opened in 1870 to accept deposits from the Comstock Lode and to mint coins. During its operation, it produced eight different coin denominations. Congress withdrew its mint status in 1899 when the Comstock's ore declined, but it continued as an assay office until 1933.

Fort Knox:

The Mint's demand for the gold and silver needed to produce coins in increasing quantity for the growing U.S. population meant that there needed to be a secure location to store the country's bullion. In 1936, the Fort Knox Bullion Depository opened in Kentucky.

Today:

The Mint maintains production facilities in Philadelphia, San Francisco, Denver, and West Point, and a bullion depository in Fort Knox.

U.S. circulating coins began long before the opening of a national mint in 1792. Before national coinage, a mix of foreign and domestic coins circulated, both during the Colonial Period and in the years following the Revolutionary War. After Congress established the U.S. Mint in 1792, the Mint struggled for many years to produce enough coins. Finally, production numbers grew to meet the demands of a growing nation, providing some of the most beloved circulating coin designs.

Colonial Period:

During the Colonial Period, a variety of coins circulated, including British pounds, German thalers, Spanish milled dollars, and even some coins produced by the colonies. Spanish milled dollars became a favorite because of the consistency of the silver content throughout the years. To make change for a dollar, people sometimes cut the coin into halves, quarters, eighths, and sixteenths to match the fractional denominations that were in short supply.

After the Revolutionary War:

The Articles of Confederation governed the country. The Articles allowed each state to make their own coins and set values for them, in addition to the foreign coins already circulating. This created a confusing situation, with the same coin worth different amounts from state to state.

Fugio cents:

In 1787, after much debate about national coinage, Congress authorized the production of copper cents. Called Fugio cents, the coins featured a sundial on the obverse and a chain of 13 links on the reverse. However, the following year, a majority of states ratified the Constitution, establishing a new government and creating a new debate over national coinage.

Coinage Act of 1792:

The Coinage Act of 1792 established a national mint located in Philadelphia. Congress chose decimal coinage in parts of 100, and set the U.S. dollar to the already familiar Spanish milled dollar and its fractional parts (half, quarter, eighth, sixteenth). This resulted in coins of the following metals and denominations:

- Copper: half cent and cent

- Silver: half dime, dime, quarter, half dollar, and dollar

- Gold: quarter eagle ($2.50), half eagle ($5), and eagle ($10)

March 1, 1793:

In 1792, during construction of the new Mint, 1,500 silver half dimes were made in the cellar of a nearby building. These half dimes were probably given out to dignitaries and friends and not released into circulation. The Mint delivered the nation's first circulating coins on March 1, 1793: 11,178 copper cents.

These new cents caused a bit of a public outcry. They were larger than a modern quarter, a bulky size for small change. The image of Liberty on the obverse showed her hair steaming behind her and her expression "in a fright." The reverse featured a chain of 15 links, similar to the Fugio cent. However, some people felt that it symbolized slavery instead of unity of the states. The Mint quickly replaced the chain with a wreath, and a couple months later designed a new version of Liberty.

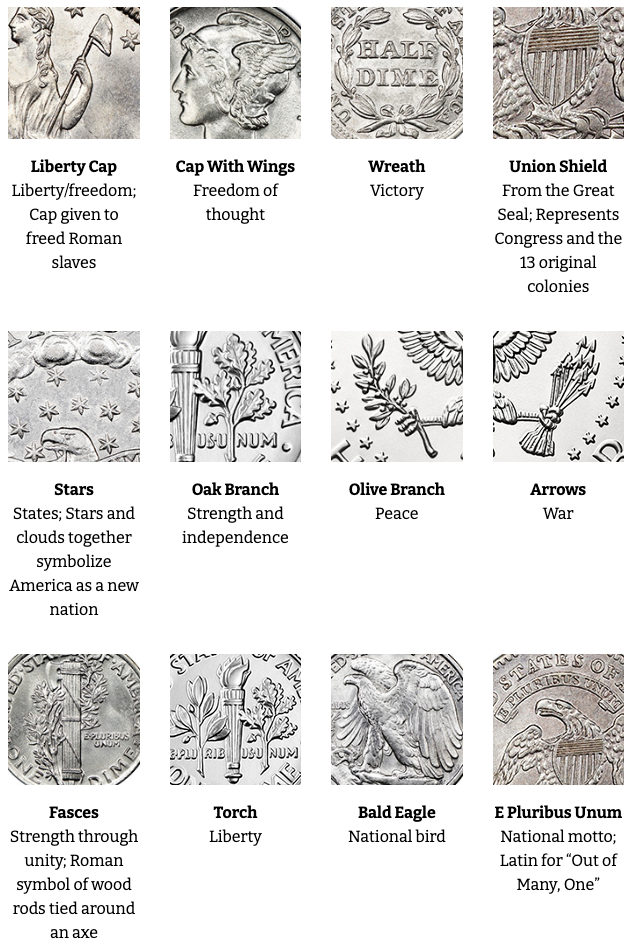

Symbols on Coins:

Early and modern US coins are full of symbolism. Many symbols have ancient Greek and Roman origins and were widely used in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Hamilton was America's first treasury secretary, of course, from 1789 to 1795. But in many ways he's also the inventor of American money: He encouraged the use of the dollar bill as the basic unit of currency and called for a series of coins broken into smaller values, a new concept in an age when bartering was the preferred method of transaction. To encourage the new American spirit, he recommended putting presidential faces on the money. Since there was only one president at that time, this meant the basic unit currency went to Hamilton's good friend George Washington.

The Treasury Department Building is on the back

https://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2015/06/ten-facts-about-alexander-hamilton-on-the-10-bill.html

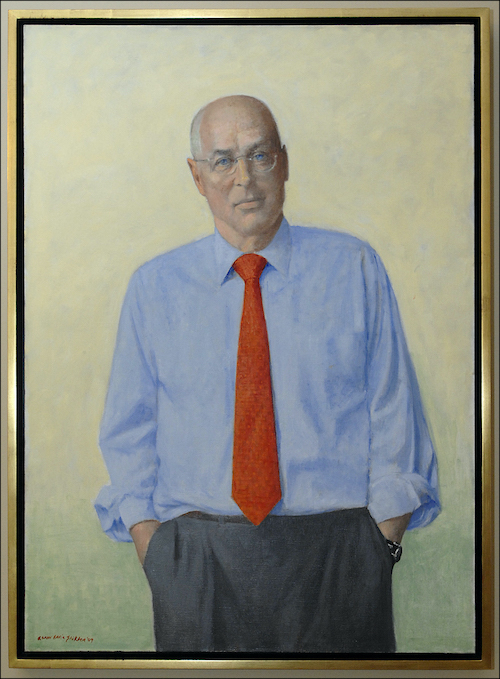

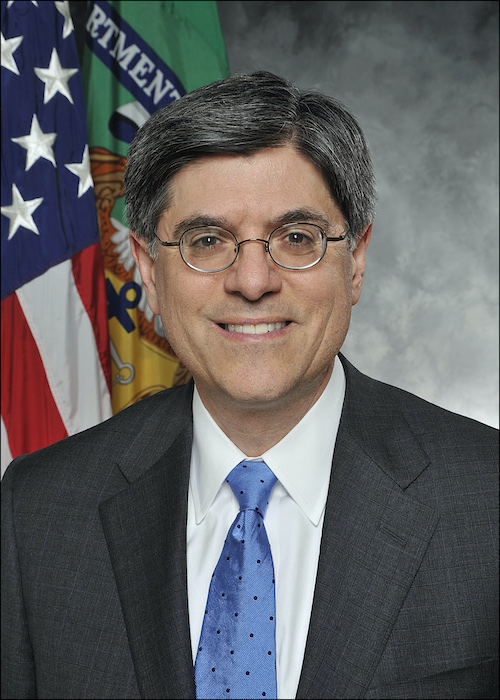

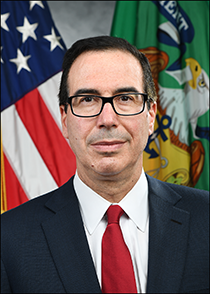

| Prior Secretaries: |

|---|

| https://home.treasury.gov/about/history/prior-secretaries |

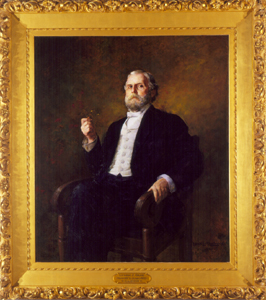

Alexander Hamilton At the inauguration of the constitutional government in 1789 Alexander Hamilton (1757- 1804), George Washington's former military aide and a renowned financier, was appointed the first Secretary of the Treasury and thus he became the architect of the structure of the Department. Desirous of a strong, centrally controlled Treasury, Hamilton did constant battle with Thomas Jefferson, then Secretary of State, and Albert Gallatin, then a Congressman, over the amount of power the Department of the Treasury should be allowed to wield. He designed a Treasury Department for the collection and disbursing of public revenue, but also for the promotion of the economic development of the country.1789 - 1795 (President Washington) Facing a chaotic treasury burdened by the heavy debt of the Revolutionary War, Hamilton's first interest when he took office was the repayment of the war debt in full. "The debt of the United States ... was the price of liberty,'' he affirmed, and he then put into effect, during 1790 and 1791, a revenue system based on customs duties and excise taxes. Hamilton's attack on the debt helped secure the confidence and respect of foreign nations. He introduced plans for the First Bank of the United States, established in 1791 which was designed to be the financial agent of the Treasury Department. The Bank served as a depository for public funds and assisted the Government in its financial transactions. The First Bank issued paper currency, used to pay taxes and debts owed to the Federal Government. Hamilton also introduced plans for a United States Mint. Though he wanted the Mint to be a structural part of the Treasury, he lost the battle to Jefferson and it was established in 1792 within the State Department. The Mint became an independent agency in 1797 and was eventually transferred to Treasury in 1873. Under personal financial pressure, his office paying only $3500 a year, Hamilton resigned in 1795 and joined the New York bar. He kept in close contact with President Washington, however, and continued to give financial advice to his successor, Oliver Wolcott. Hamilton was killed in 1804 in a duel with Aaron Burr arising from a political dispute. |

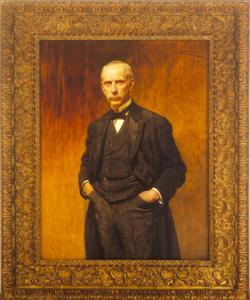

Oliver Wolcott, Jr. Beginning in 1789, Oliver Wolcott Jr. (b.1760 - 1833) played an important role in the organization of the nascent Treasury Department. First, as Auditor, he established its clerical forms and methods, and two years later, as Comptroller, he was instrumental in establishing the branches of Secretary Alexander Hamilton's First Bank of the United States. In 1795 Wolcott was appointed by President Washington to be Hamilton's successor, continuing as Secretary under President John Adams. Charged with the task of raising revenue for the rapidly growing Federal Government, Wolcott constantly sought and received Hamilton's advice. As Hamilton's ally he faced difficulties in Congress, where Hamilton's opponent Albert Gallatin sought more congressional control of Treasury's financial policy. Wolcott resigned in 1800 under a storm of criticism from Jeffersonians in Congress. In reaction he invited a congressional investigation of the Treasury Department in 1801, which cleared his name.1795 - 1800 (President Washington, President John Adams) |

Samuel Dexter Educated at Harvard and trained as a lawyer, Samuel Dexter (1761 - 1816) resigned his seat as Massachusetts Senator in June 1800 to accept the position of Secretary of War in the Cabinet of President John Adams. Upon Secretary of the Treasury Oliver Wolcott's resignation in December 1800, Adams appointed Dexter an interim Secretary to serve until the inauguration of Thomas Jefferson as President. Dexter served less than a year in Adams' Cabinet and has no great acts associated with his name. It has been said that "his temperament and intellectual endowment ill suited him for that minute diligence and attention to intricate details which the departments of War and Finance imposed on the incumbents of office."1801 (President John Adams, President Jefferson) Shortly before the termination of Adams' Administration, the President offered Dexter a foreign embassy, but Dexter declined, remaining at the Treasury Department until Jefferson became President. |

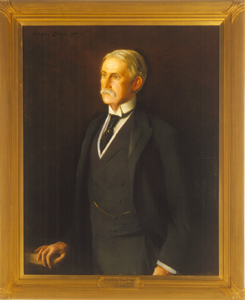

Albert Gallatin Elected to the House of Representatives in 1795 and serving until 1801, Gallatin fought constantly with the independent minded first Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton. He was responsible for the law of 1801 requiring an annual report by the Secretary of the Treasury, and he submitted the first one later that year as Secretary. He also helped create the powerful House Ways and Means Committee to assure Treasury's accountability to Congress by reviewing the Department's annual report concerning revenues, debts, loans, and expenditures. Appointed Secretary of the Treasury in 1801 by President Jefferson and continuing under President James Madison until 1814, Gallatin was in office nearly thirteen years, the longest term of any Secretary in the Department's history.1801 - 1814 (President Jefferson, President Madison) As Secretary, he followed a Hamiltonian course, establishing the independence of the Secretary of the Treasury and institutionalizing the Department structures. Gallatin considerably reduced the federal debt by setting aside revenue for that purpose, and he revived internal taxes to pay for the War of 1812 but they were not sufficient. Having failed to convince Congress to recharter the First Bank of the United States in 1811, and foreseeing financial disaster, he resigned in 1814. That year Gallatin went to Russia to represent the United States in the peace conference with England and France settling hostilities. The outcome of the conference was the Treaty of Ghent signed in 1814. |

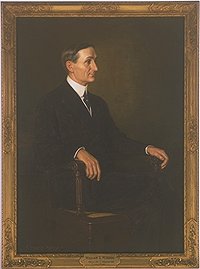

George W. Campbell Born in Scotland, George W. Campbell (1769 - 1848) moved with his family to North Carolina in 1772. When President Madison appointed him Secretary of the Treasury in 1814, he became the first Cabinet member from a region west of the Appalachian Mountains.1814 (President Madison) Campbell entered office during the War of 1812 and the state of the Nation's finances was in serious disorder. Congress had failed to recharter the First Bank of the United States after its charter expired in 1811 and had not made appropriations to finance the War of 1812. Campbell's most perplexing problem was convincing the American people to buy government bonds to pay for the war. Much of the Nation's money was concentrated in New England, which was opposed to the war, and though Campbell put up bonds for sale and begged northern bankers to subscribe, he could not inspire their confidence. He was forced to meet to lenders terms, selling government bonds at exorbitant interest rates. In September 1814 the British occupied Washington and the credit of the Government was lowered even further. Campbell was unsuccessful in his efforts to raise money through additional bond sales and he resigned that October after only eight months in office, disillusioned and in bad health. |

Alexander J. Dallas When Alexander Dallas (1759 - 1817) was appointed Secretary of the Treasury by President Madison in 1814, he was faced with a bankrupt Treasury depleted by the War of 1812 and with an unstable currency situation caused by the proliferation of commercial banks and their worthless bank notes not backed by specie. In a report to Congress in 1814, Dallas advocated permanent annual revenue to be raised by internal taxes, in addition to the external revenue already derived from Customs duties. He also advised the creation of the Second Bank of the United States to supply financial resources to an embarrassed Treasury and regulate bank note circulation.1814 - 1816 (President Madison) The revenue measures elaborated in this report mark the beginning of a conflict between advocates of internal revenue and those of solely external revenue. This conflict continued until the imposition of the income tax in 1913. Excise taxes, established in 1813 as a temporary wartime measure, continued to be collected until 1817. In addition, Congress enacted a high external tariff in 1816 to help pay the war debt. Dallas succeeded in his efforts to establish the Second Bank of the United States, which was chartered by Congress in 1816. He retired that year after the new Bank had been organized. |